When Charlie de Haas, 32, became a fitness model

in her mid-20s she thought blitzing her body fat to

six per cent would solve her image problems. But it only made things worse. The harder she worked out and the more she dieted, the more her obsession with her flaws escalated.

When Charlie de Haas, 32, became a fitness model

in her mid-20s she thought blitzing her body fat to

six per cent would solve her image problems. But it only made things worse. The harder she worked out and the more she dieted, the more her obsession with her flaws escalated.

“I’d look in the mirror and analyse my body every single day,” she says. “I’d find every little line or definition and if I found cellulite or stretch marks or a grey hair or a wrinkle, I would think, ‘What is this?’”

For Charlie, her appearance became all-consuming. “Every morning I’d check out my body in the mirror from every angle and I’d do it again at night,” she recalls.

“I’d decide what part of my body wasn’t good enough, then I’d over-workout because I had this belief that I wasn’t good enough until I got it right.” these days Charlie understands that she was in the grip of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) as well as an eating disorder that resulted in her suffering from debilitating adrenal fatigue.

“I didn’t realise at the time how small I was,” she says. “My friends told me they were concerned about me and now when I look at the photos I can’t believe I looked like that,” says Charlie.

BDD is classified as an anxiety disorder and it’s believed to affect one to two per cent of the population. It’s a mental illness that causes people to worry incessantly about the way they look. They often lose hours a day checking their reflection or working out in pursuit of the ‘perfect’ body, and, in extreme cases, withdraw from social settings or work because they feel they are too hideous.

“It might be their nose, their skin or even the length of their arms,” explains Clinical Psychologist Dr Ben Buchanan. “People with BDD believe that one or two areas wreck their entire appearance.”

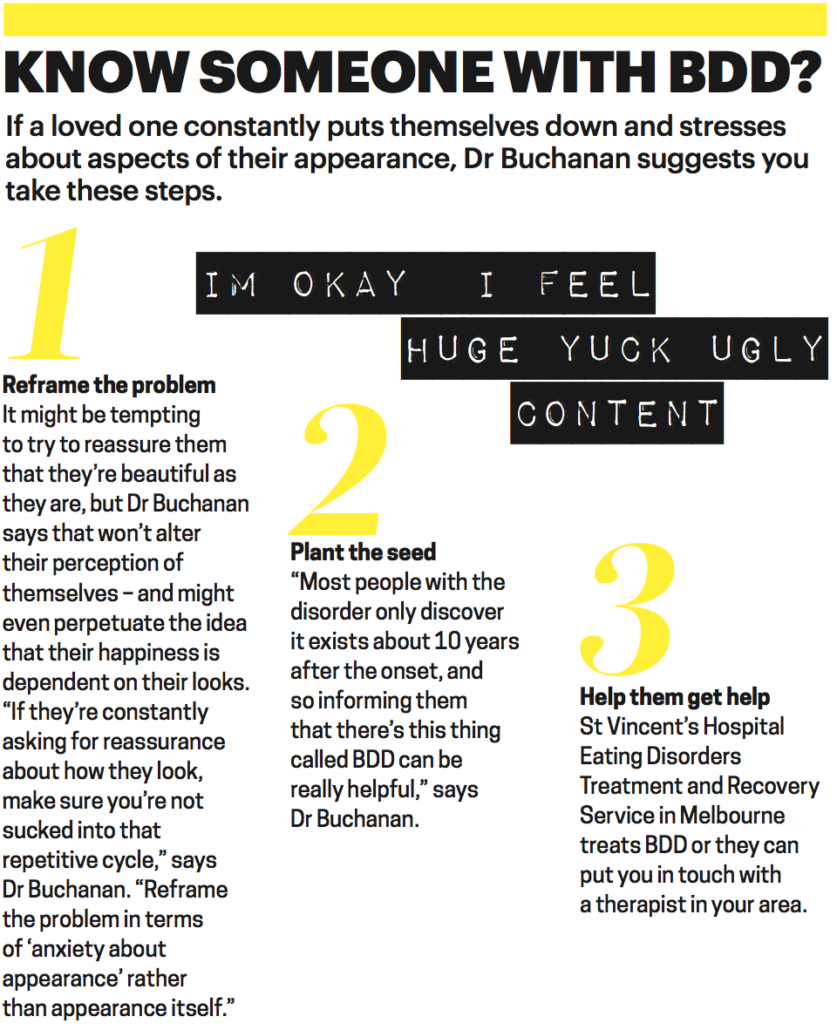

While most of us can name a feature or two that we wouldn’t mind improving, Dr Buchanan says that sufferers of BDD are completely consumed by their perceived flaw. “ The difference between normal body image concerns and body dysmorphic disorder is repetitive and ritualistic behaviours,” explains Dr Buchanan. “Someone with BDD might mirror-check for hours every day and constantly measure or weigh themselves or compare themselves to other people in real life or those on social media. Sometimes they’ll spend a couple of months or even years at a time fixated on one aspect of their appearance then it might shift and they’ll become concerned about a different aspect.”

How it happens

Similar to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), a lot of behaviour associated with BDD is a result of misfiring in the amygdala region of the brain, which controls our emotions. “It’s the part of the brain that sounds an alarm and makes us stressed if things aren’t right,” says Dr Buchanan. Ordinarily the amygdala lights up in response to a stressful situation, but Dr Buchanan says brain scans show it lights up randomly in sufferers of BDD, who then seek to attach something to the stress.

“They get super stressed out and search for a reason why. For whatever reason, people with BDD attach that stressed-out feeling to how they look,” he says.

Research shows that people with BDD also have incredible attention to detail. “ there’s a test you can give people where you show them an image that’s supposed to be symmetrical but it’s not quite. People with BDD are fantastic at picking out slight asymmetries because they’re very detail- oriented,” says Dr Buchanan.

Professor Susan Rossell, director of Swinburne University Centre for Mental Health, says that people with BDD also appear to have something wrong with their visual system. “When [most] people look at the world or in the mirror they take in everything as a whole, whereas people with BDD process visual information in a very fragmented way,” she explains.

“It’s like they see a jigsaw puzzle but they haven’t put it together ‒ they see the little pieces and become very focused on a single thing and they take it out of context.”

BDD affects men and women equally. It can run in families, and people who have grown up with controlling parents or as a victim of childhood bullying appear to be at higher risk. “Having instances of teasing about one’s appearance in childhood is usually associated with the disorder,” Dr Buchanan explains. “I also see patients whose parents valued looks over everything else. If the only compliment a child receives is that they look nice or if parents are always criticising appearance, a person can associate their self worth with their appearance,” he says.

Simply wanting to lose weight does not warrant a BDD diagnosis. “A person with BDD may experience a significant amount of distress or become seriously anxious if they can’t count their points or they become super harsh on themselves and think they’re a failure if they go over their SmartPoints allowance or eat too much,” Dr Buchanan says. “People with BDD really struggle and it takes over their life completely.” Historically, sufferers of BDD flew under the radar but with advancements, popularity and availability of cosmetic surgery the true extent of the problem has emerged.

“It started to get taken seriously when medicine improved and there was a big in flux of plastic surgery,” Professor Rossell explains. “People with BDD would go and have surgery even though they’re absolutely beautiful and they’d often ruin [their appearance].”

Cosmetic surgeons are now trained to look for symptoms of BDD and help identify people at risk. “Stats show that 84 per cent of people with BDD who get plastic surgery will be really disappointed and it won’t improve their life,” Dr Buchanan says. “It won’t make them happier and often it back fires and they think that their ears or nose or whatever they have had altered looks even uglier.”

In stark contrast to the rest of the population. “Most people who get plastic surgery are a bit happier afterwards but if you have BDD, or the warning signs of it, then cosmetic surgery, including liposuction and weight-related surgery, can be really risky,” stresses Dr Buchanan.

The fact that BDD is still not widely known about or understood by the general public means sufferers may endure the condition for years without recognising it. “Most people with BDD won’t realise they’ve got it – they actually think they’re ugly,” Dr Buchanan points out. Meanwhile family members and friends can easily dismiss a person’s obsession with their appearance as vain.

“Psychologists don’t often see people until many years down the line because they’ve engaged with dietitians, dermatologists and cosmetic surgeons to deal with their body image issues rather than facing the psychological issues about their body image,” says Professor Rossell.

One of the simplest ways for sufferers to start to understand they may have BDD is to consider how their assessment of their appearance compares to what others think of them. “Do people around you say, ‘Why are you on a diet? You have a beautiful figure.’ Or, ‘Why do you need to lose weight, you’re the perfect size and shape,’” says Professor Rossell. If your assessment of yourself is at odds with those who love you, it may be an indication you have BDD.

Promising prognosis

While it may be hard to admit that you’re ashamed of your appearance, if you think you, or someone close to you, may have BDD, Dr Buchanan suggests finding a psychologist with specific experience treating the disorder. Treatment may involve cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which helps change unhelpful thought patterns.

“CBT essentially retrains the brain to not buy into the thoughts that BDD feeds the individual,” says Dr Buchanan. the good news is that the prognosis is good if you use CBT.

“BDD is certainly treatable – after 12 sessions, more than half of people will no longer have the disorder,” says Dr Buchanan. Some patients are put on antidepressant medication, which Dr Buchanan says has a 50 per cent success rate.

For Charlie, treatment for the disorder has been an ongoing process that’s required a complete change in mental processes. She started studying nutrition and learnt about wholesome eating, which directly contradicted the severe diet she was following during her fitness-modelling career. “I also created a couple of mantras that I use every day, which are, ‘I am happy and I am healthy’ and, ‘I am loved, I am loveable, I am loving’,” says Charlie, who now runs Clean Treats, a healthy snack food company. “Instead of thinking ‘I’m fat’ or ‘there’s a grey hair’, I look in the mirror and say ‘I love you’. It’s my way of telling myself I have my own back and it creates a sense of strength.”

This Body Dysmorphic Disorder article was originally published in Weight Watchers Magazine. Written by Kimberly Gillan.